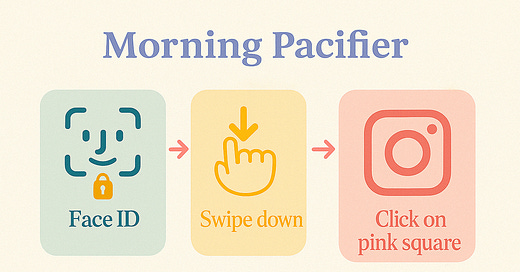

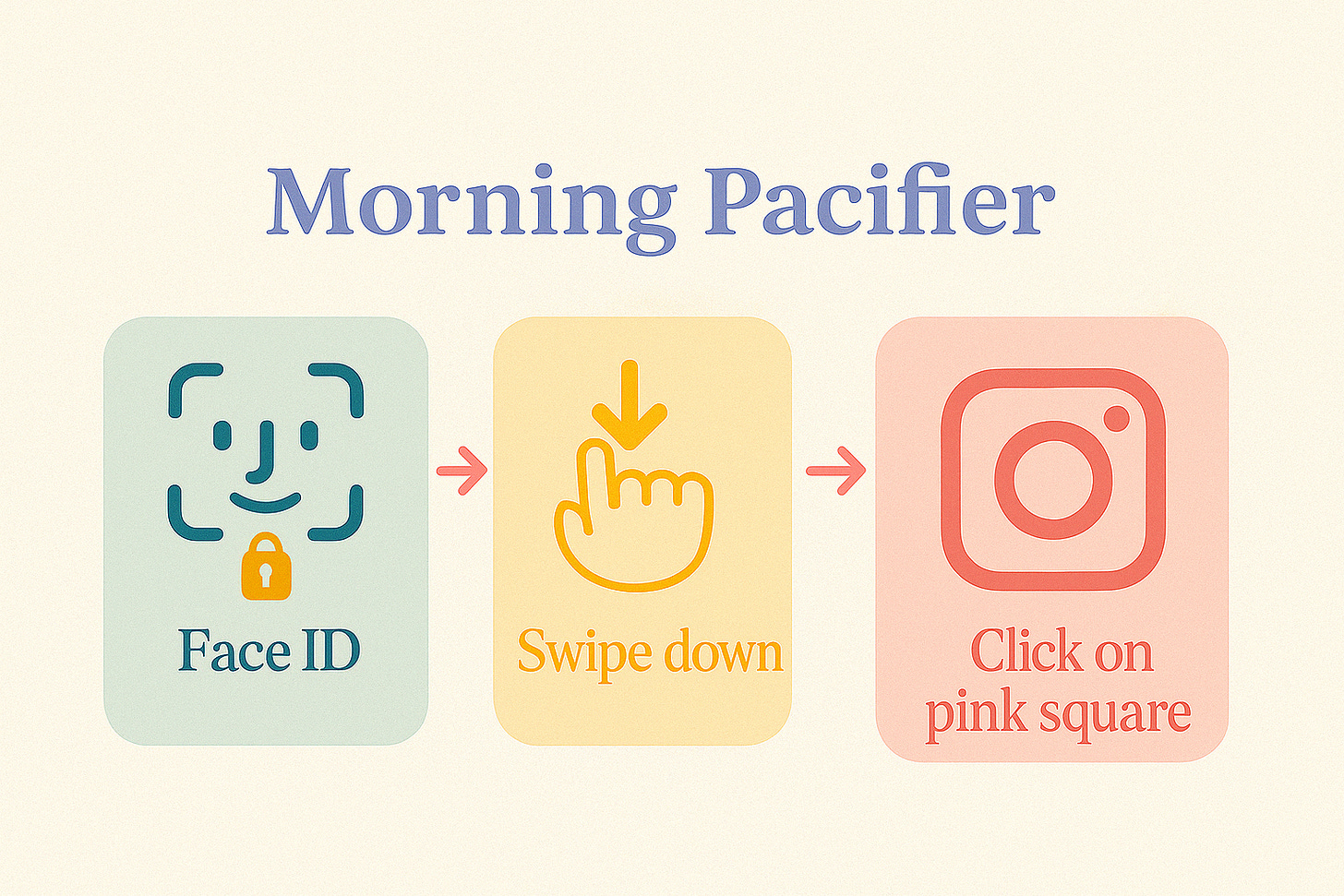

I woke up and put on my pacifier with a mindless shortcut—[Face ID -> swipe down -> click on pink square]—a habit so ingrained in my brain that it didn’t register. A few minutes later, I found myself deep in a hole of feet-strengthening reels, followed by a string of feet-strengthening ads, before I accidentally came up for air and realized how little of my feed was generated by actual friends. Now, after discovering how to stop suggested content, I’ve bought 30 days of air before the algorithm drags me back under.

Modern social media has become a game of attention rather than connection. What started as a way to keep us in touch with others has turned into an ecosystem designed to keep us engaged, swiping, and scrolling. The problem is that connection has become secondary to retention & ad funnel optimization. I don’t blame Meta, X, LinkedIn, or Snapchat—the pursuit of growth was and is needed to attract funding and please shareholders. Once user growth slows, they have no choice but to extract more from their existing user base. I’m not against monetization (or capitalism), but monetization should come from providing more value. The question is: what do we define as valuable? Maybe more personalized Instagram ads are valuable because they help people buy goods that better align with their identity. I’d argue that prioritizing real-world relationship-building is better aligned with long term fulfillment than material goods are, and thus “more valuable”. Naturally, when the goal is to keep people on the app, designing for real-life connection outside of the app takes a backseat.

I’m far from the first person to think about this; plenty of smart people have tried to tackle the problem. A few are showing signs of success, like Beli or Strava, which build community around real-world activities. A few more are in the void, like BeReal, which pushed for authenticity but ultimately failed to maintain engagement because its novelty wore off without a hook to keep people engaged. Many more failed and are merely figments of our memories. They all recognize the same fundamental issue—social media should be a bridge to real life, not a replacement for it.

I believe that technology can help solve the loneliness epidemic at scale, but it feels like nothing has worked at the level needed. Sometimes that makes me pessimistic—if so many talented people have tried and failed, maybe technology and community are just antithetical to each other. Instead of accepting that, I want to dissect why. What's missing? Where do these platforms break down? And is there still an opportunity to get this right?

The Bumble BFF Problem

When I moved to Boston, I didn't know many people, so I tried anything I could to make friends. As a part of this journey, I got on Bumble BFF. My female friends had told me of past success stories, so I decided to give it a try.

I'd wager that most of the men reading this have never tried Bumble BFF. And, from firsthand experience, for good reason. Have you heard of a "normal" guy using Bumble BFF (defining normal is a topic for another day)? It's like there's negative network effects, where any normal guy interacts with less normal guys, leading them to get off the app and leaving only the less normal guys on. I'd argue most of the current platforms meant for in-person socialization come with this "normality" problem. This underscores why proper vetting is essential—it creates the foundation of trust needed for meaningful social connections to form. Some platforms, like Timeleft, an app for random strangers to get together for dinner every Wednesday night, are halfway to solving this quality problem. They have personality quizzes in an attempt to bring groups of people together & have the connection stick. However, people who already have a community don’t go searching for one. So, by default, you self-select the people who truly need or want something in order to make it successful. The challenge becomes: how do you bring in people who don't need something, but just want it?

On top of vetting is context. With Bumble BFF (or even Hinge), every profile was a collection of generic interests: "I love hiking, trying new restaurants, and my dog." When everyone says the same thing, no one stands out, and there was nothing to anchor a conversation. Worse, even when I matched with people, nothing happened. No one knew how to take the next step. The problem wasn't intent—plenty of people wanted to make new friends. The problem was context. Friendships rarely start from scratch. They emerge from shared experiences, mutual connections, and a sense of organic familiarity. Bumble BFF stripped all of that away, leaving people with a cold-start problem: two strangers with no built-in reason to talk or trust each other and high opportunity cost against hanging out with their existing friends. A solution needs vetting, and it needs to appeal to those that already have community, which means it must first be useful to maintain community instead of building it.

The best in-person interactions can still be random – I met all my friends in Boston from house parties – my idol event for socializing in our 20s. House parties come with both vetting and context – there's a higher baseline of trust because everyone is somehow connected to everyone else, and there's a higher chance that you have similar interests and values compared to this relatively homogeneous group of people. Adding DJs to the house parties I throw creates space for an activity (dancing) while also leaving room to talk and get to know people. The parties feel natural because they happen within trusted networks or shared environments.

The Power of Shared Experience

Once a baseline of trust and safety is established, what makes an interaction feel magical? Dancing at house parties offered the first glimpse of the answer.

Our most meaningful relationships don't form in a vacuum—they emerge from the foundations of shared experience. Look at your closest friendships: they likely originated from time-based contexts (childhood friends, college roommates) or activity-based ones (teammates, college org members). These bonds stick because of continuity—repeated, meaningful interactions that build trust.

This is precisely what's missing from most social platforms. In school, we saw the same people daily, creating natural opportunities for relationships to evolve. In adulthood, this continuity dissolves, and we're left searching for substitutes. The platforms that succeed are those that recreate this natural rhythm of repeated shared experiences.

Strava works because it's built community around literal real world activity. Cold plunge events, like Plunge Party in SF, succeed because they bring people together around an activity that is both challenging and rewarding. The magic ingredient isn't just meeting people—it's doing something meaningful with them.

How to Make Magic

Of course, this is where scale and community could be at odds, and it’s a potential catch-22 I’m still thinking through. Failed tests include SoHo House, which had to focus on growth, especially after going public, meaning that the people who made it desirable in the first place no longer found it authentic to what it was and self-prescribed implosion ensued.

There are some interesting solutions, like Matchbox, which hosts in person dating events in NYC but also sells a subscription to their matchmaking and event hosting platform for other hosts to do the same. Spread, a new information sharing platform, authenticates all users as humans to open up access to otherwise paywalled content. Their bet is that proof of humanity will differentiate the social experience and unlock new business models for publishers. Hopefully it'll be magical enough to withstand the app fatigue all face today.

I like these creative business models because unlike traditional social media, they monetize the platform without the consumer being the end product, allowing for both a pure customer experience and a scalable business. The next wave of consumer social will either monetize by providing the consumer so much value they’re willing to pay for it or find other, business or community based, paths to monetization.

Building The Future of Consumer Social: A Return to Real Life

The future of consumer social isn't about optimizing engagement or capturing attention—it's about helping people spend their time more meaningfully. The next wave of successful platforms will be those that facilitate real connection, using digital tools as a means to an end, not the end itself.

To get there, social apps must focus on three key pillars:

1. Quality Onboarding – The strongest communities start with people who already have one. Platforms should first help users maintain meaningful connections before trying to manufacture new ones at scale.

2. Design for Loops, Not Moments – A single great interaction is a spark, but real relationships are built through repeated, low-friction touchpoints over time. The best platforms don’t just introduce people—they give them a reason to keep showing up.

3. Non-Extractive Monetization – The most enduring consumer social businesses create value with their users, not from them. Magic happens when monetization aligns with user well-being, not their attention span.

This is what I'm thinking about, but more importantly, I'm looking for people who are already working on this—founders, builders, anyone experimenting in this space. If that's you, I’d love to talk. If we can get this right, we can solve one of the biggest problems our society faces, the loneliness epidemic, and the whole host of second order problems that stem from it (e.g., mental health, polarization). The next generation of social media won't be about consuming—it will be about living.

morning pacifier metaphor>>

dope of you for sharing this with the world